Both in India and in the West, there are a lot of misconceptions about the word “tantra” and the tantric practices of Hinduism and Buddhism. There are a lot of different ways to look at tantric traditions, from how they are seen as paths to freedom to how they are often linked to sorcery and sexual freedom. In the same way, tantric traditions are very different, making it hard to come up with a description that covers all of them without being too broad.

Numerous attempts have also been made to determine the origins of tantric traditions. Although there is scant evidence to support the hypothesis that tantric traditions existed prior to the fifth century CE, attempts have been made to trace these traditions back to the time of the Buddha, ancient Hindu sages, or even to the Indus Valley civilization. After looking at the different attempts to date these traditions, it seems that the first distinct tantric traditions appeared in a Hindu context around the middle of the first millennium CE.

Because there aren’t many historical records from South Asia from the first half of the first millennium CE, it’s hard to say when exactly tantric traditions started in India. As we will see in the next section, there is evidence that the first tantric practices came from the Vaishnava school of Hinduism around the year 500 CE.

Tantrism or the tantric traditions

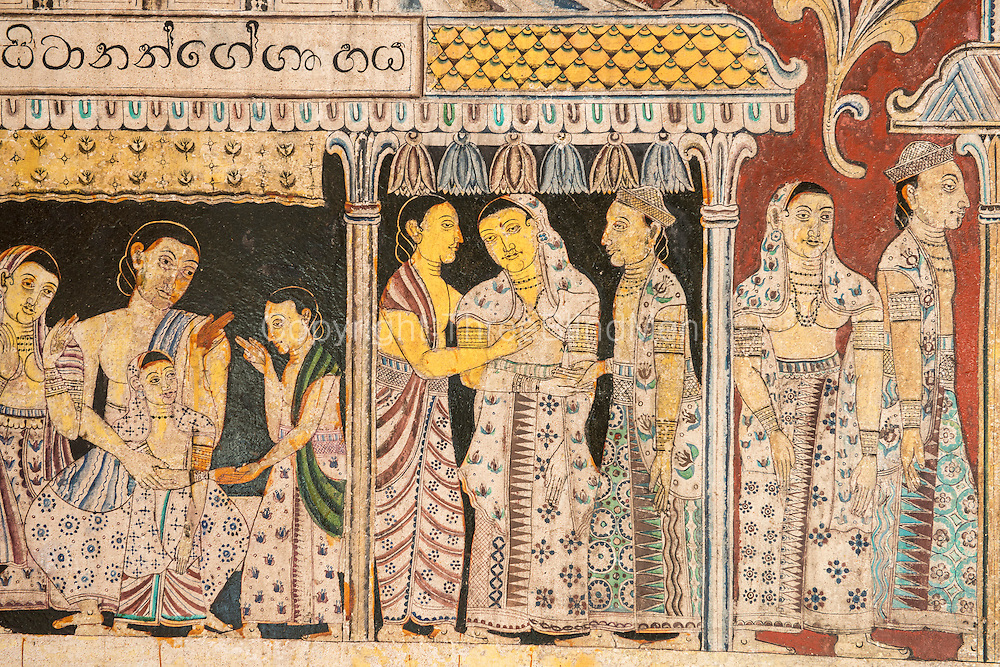

“Tantrism,” or the tantric traditions, evolved from Hinduism during the first millennium C.E. in Bundelkhand, India, and other places, tantric traditions spread and grew. There are also indications of state support from the Khmer Empire of Cambodia. Even though there were more pictures of female goddesses, Samuel said that these tantric traditions seemed to have been mostly “male-directed and male-controlled.”

The spread of tantric traditions followed swiftly after their emergence in India. They were spread to Nepal, Central, East, and Southeast Asia, and eventually to the West. Tantric Hindu and Buddhist traditions also had an effect on Jainism, Sikhism, the Bon tradition of Tibet, Daoism, and the Shinto tradition of Japan, among others.

Over the course of this millennium, Hinduism went through a remarkable series of changes, moving from the ancient Vedic tradition to its classical traditions. During this time, both the tantric and Bhakti devotional movements flourished. Tantra grew out of ritual practices from the Vedas as well as yogic and meditative practices from ancient Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, which were at odds with each other. Hinduism, as it is practiced today, came about when tantric and devotional practices were mixed together in the first millennium CE.

Till date most Hindus and scholars don’t fully understand the connection between modern Hindu practices, like the daily worship ceremonies that many Hindus do in private shrines or public temples, and tantric traditions. This is because, until recently, most people didn’t pay much attention to the rich liturgical literature that Hindu traditions have produced.

Even though tantric traditions have affected most Hindu traditions in some way, this article will focus on those Hindu traditions that categorically call themselves tantric. Tantrism, despite having originated in a Hindu context, is not exclusive to Hinduism. Early Hindu tantric practices had a big impact on South Asian Mahyna Buddhist practices, which led to the creation of tantric practices that are unique to Buddhism. They also had less obvious but still important effects on Jainism and a number of other religions. In the seventh century CE, Buddhist tantric traditions spread quickly to Southeast, East, and Central Asia. This led to the development of a number of unique East Asian and Tibetan traditions. In Tibet, these things led to the growth of Daoism, Shintoism, and the Bon tradition.

Tantric Tradition Depicted As Dirty Practice

The tantric traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism have been both notorious and poorly comprehended. Tantric traditions have been linked to black magic in India for at least the past few hundred years. This is because tantric practices are strongly linked to magic, and “left-handed” (vmcra) tantric practices are linked to sexuality and violent rituals.

Tantric traditions have had a significant impact on the practice of Hinduism that is currently underappreciated by most Hindus; the term “tantra” is now best known in South Asia in the compound “tantra-mantra,” which is the equivalent in modern languages such as Hindi to “abracadabra” or “hocus-pocus” in English, terms that originated in Western magical practices and now designate “mumbo-jumbo, nonsense, or gibberish,” and “magic, trickery, or A recent Hindi horror film involving black magic was given the name Tantra Mantra.

In modern Indian languages, the word “tantra” is often linked to powerful black magic, sexual activity that is against the law, and bad behavior. Western experts on Indian culture and history often look down on tantric traditions and use the idea that they are corrupt as an excuse to ignore this important part of Asian religious history.

Yoga is a healthy and sophisticated way to work out, and most women in the Western world do it. Historically, however, yoga and tantric sex have had a very close relationship, as William Broad of the New York Times noted:

The practice originated as a sex cult. Hatha yoga, the ancestor of the styles now practiced worldwide, originated as a branch of Tantra. Hatha was created to expedite the Tantric agenda. It utilized postures, deep breathing, and stimulating acts, including intercourse, to hasten ecstasy.

Some yoga poses have a clearer connection to Kamasutra-style sexual relations than others. For example yoganidrasana, is one of the most provocative poses a woman can do when she’s naked. Yoganidrasana makes it possible for the yoni (vagina) to be deeply penetrated. If a man is strong enough, this can set the stage for a long, very satisfying copulation. There are many such poses described in tantra that make sex exciting and blissful when done in the correct form as per the directions.

The Kama Sutra says that men can be put into different groups based on the size of their penis, which is called a “lingam” in Sanskrit. A person with a small penis is called a “horse-man,” a person with an average-sized penis is called a “bull-man,” and a person with an abnormally large penis is called a “horse-man.”

Likewise, females can be categorized based on the size of their yoni or vagina. A woman with a small yoni is referred to as a deer, while one with an average-sized yoni is referred to as a mare, and one with an unusually large yoni is referred to as an elephant. The Kama Sutra describes nine types of Tantric union, one for each combination of the three lingam types and the three yoni types.

Tanta and Meditation

Traditional Buddhist Tantra employs sexual symbolism as a meditation aid. Hindu tantric engage in sexual rituals for spiritual purposes. As a means of “weaving” the physical and spiritual, Buddhist and Hindu meditators may also engage in tantric sex.

This practice combines spirituality and sexuality and highlights the significance of intimacy during a sexual encounter. However, tantra is not solely concerned with sexual pleasure. It is more about embracing your body and experiencing intensified sensuality. The technique combines spirituality, sexuality, and a contemplative state. It encourages a sensual experience that can be shared or enjoyed alone.

In modern times, Tantra has been mixed up with the sexual ideas of paganism, Taoism, and other esoteric religions. The concept of tantric sex originated in ancient Hinduism based on unique and fundamental scientific reasoning. Tantric sex is a slow, meditative form of sex in which the end goal is not hedonism but rather the enjoyment of the sexual journey and body sensations. It tries to get sexual energy to flow through the body so that healing, change, and enlightenment can happen. Advocates of tantric sex think that tantric techniques can help treat sexual problems like ejaculating too early, not being able to get an erection, and having a strong urge to pee.

Understanding the body

Tantric sex encourages individuals to become acquainted with and in tune with their bodies.

If you know what your body wants, you can include it in your sexual encounters with a partner. This may result in increased sexual satisfaction and more intense orgasms. To understand what the body wants, it can be helpful to practice tantric self-love or masturbation. If a person has emotional barriers to self-touch, they should be curious and gentle with themselves as they investigate what is preventing them from knowing their own.

body more closely. The more a person knows about their body and pleasure zones, the more satisfying their sexual experience will be. If a person does not wish to engage in masturbation and has a partner, they may feel more at ease learning about their body through partnered sex.

Knowing one’s partner’s body.

Tantric sex involves respecting one’s own and one’s partner’s bodies. By taking the time to learn about one’s own body and that of one’s partner, the experience can be more fulfilling for both parties. A person may consider giving their partner a slow, full-body massage in order to learn more about their body and to stimulate their sexual energy. This may also assist a person in understanding their partner’s wants and needs. As with any sexual activity, if a person or their partner becomes uncomfortable at any point, the activity should cease.

How to get ready

A person or couple can do a number of things to prepare for tantric sex. For instance, they can say, “The more information someone has about tantric sex, the more likely they are to feel prepared.”

Tantric sex involves moving slowly and being present in the moment. In certain instances, it may last an hour or longer. Devote sufficient time to fully engage in and appreciate the experience.

Preparing the mind: It can be hard to focus on the present if a person is stressed out or has a lot of thoughts. Before engaging in tantric sex, meditating or stretching may help achieve a clear mind.

Find a good location:

The environment plays a crucial role in tantric sexuality. Ideally, it will occur in a serene environment with a comfortable temperature. A person may wish to dim the lights, light a fragrant candle, or play soothing music.

Creating the present moment for oneself:

To create a moment with oneself, one can try the following strategies:

Tantric sex encourages individuals to be present in the present moment. An individual should concentrate on their breathing and bodily sensations.

Explore the body:

Giving yourself a massage while paying attention to touch and the body can make you feel more physically alive and excited.

A person may wish to engage in tantric self-love while masturbating. Similar to partnered sex, the objective may not be an orgasm. People may do this in an attempt to feel more connected to their bodies.

Co-creating the moment with a companion:

To create a moment with a partner, individuals can try the following strategies:

To achieve a profound connection, couples should sit cross-legged and face one another with their hands on their hearts. Each partner should place their right hand on the other’s heart and their left hand on top. Feel the connection and attempt to breathe in unison.

Don’t be linear. Typically, sexual activities consist of foreplay, interaction, and orgasm. Nonetheless, tantric sex is about experimentation, so it is best to remain open to whatever feels good at the moment.

Make eye contact:

Making eye contact can help strengthen the relationship and increase intimacy.

Tantric sex is meditative and about exploring sensations in the present moment. This journey should be leisurely and enjoyable for both partners.

Tantrism was shadowed by Hindu and Other Religion

The Bhakti devotional movement also emerged in Hinduism in the early first millennium CE. Tantric traditions emerged about this time. It was monotheistic because salvation depended on allegiance to a single creator god. Hinduism’s later Upanisads from the second half of the first millennium BCE show this tendency. The Bhagavad Gita, which was written around the year 100 CE, advocates devotion to God as the only way to achieve freedom.

Devotional Hinduism’s rapid rise affected tantric traditions. Most Hindu tantric traditions are about loving God, and the Vaidava Pcartra lineage combined Bhakti and tantric practices. Because Buddhism rejects the concept of a supreme Creator God, Buddhist tantric traditions had less Bhakti effect. It may have been less, but it was still there. In Buddhism, devotion is limited to the guru, although tantric practice requires it as a principle doctrine.

Śaiva Traditions

There are three “paths” in Śaiva literature: the “supreme path” (atimrga), the “road of the mantra” (mantra marga), and the “way of the clans” (kulamantra). The Pcrthika Pupatas, Lkulas, and Kplikas, or Mahvratins, produced the Atimrga. Many tantric practices probably came from these ascetic communities, whose members wanted freedom and were said to have magical powers. The Pāśupatas were probably founded in the 2nd century CE. But the aggressive and antinomian Kplikas, who lived around the year 500, had an effect on both Hindu and Buddhist tantric lineages.

The first tantric tradition was most likely the 5th-century Śaiva Mantramrga tantric tradition. The Śaiva Siddhanta tradition was common in India during the second half of the first millennium CE, but it is now only found in South India. Non-Siddhnta Mantramrga traditions valued individual worship. Mantrapha focused on Bhairava, whereas Vidypha focused on the goddess. The Gagdhār inscription and early Mantramārga works date to the 5th century.

The Niśvāsatattvasahitā, which has come down to us in a Nepalese palm-leaf manuscript of the ninth century, was composed between the fifth and seventh centuries, and the Mūlasūtra (Nivsamla), the earliest work in that corpus, was composed between 450 and 550 AD.

Antinomian Vidyāpīha tantras stand out. They practice with female divinities known as Yogins or Kins, and they concentrate on the charnel ground, as in the ancient Kplika tradition. These works are violent and sexual. Although they were poorly preserved, Vidyāpīha tantras were popular in the 6th and 7th centuries. There is circumstantial evidence that Vidypha literature existed during this time period. Dharmakīrti’s auto-commentary on his Pramāavārtika, written in the late 6th to early 7th century, refers to non-Buddhist ākinītantras and bhaginītantras that advocate violence and sexuality.

The fourth “way” of Śaiva tantric practice, the Kulamārga or “Path of the Clans,” expanded the Vidyāpīha tantras’ sensual and transgressive activities and focused on female deities. The Kaula tradition was well known.

There are five characteristics that distinguished this tradition from other Śaiva traditions:

1. Female-male erotic ritual

2. Sanguinary rituals for the ferocious gods Mahābhairava/Bhairava and Cāmu.

3. The belief that yogic extraction of essential essences can grant supernatural powers.

4. Drinking sanctified liquor initiates

5. Possession’s importance

By the 9th century, the Kaula tradition was well established. It spawned the related Śākta tradition. It created four famous subtraditions. The goddess Kulevara and Kulevar were emphasized in the eastern transmission. The Trika tradition focused on Parā, Parāparā, and Aparā, three goddesses. The Northern transmission featured the fearsome goddess Guhyakālī; the Krama tradition focused on Kālī.

The Western transmission venerated the hunchbacked goddess Kubjikā, while the Southern transmission venerated the lovely goddess Kāmeśvarī or Tripurasundarī. By the 9th century, Kashmir had these traditions. The Trika and Krama traditions were important because they didn’t see a clear line between god and practitioner.

The Nondual School of Kashmir Shaivism emerged in the 10th century. According to a few historians, the traditional Śaiva Siddhanta tradition and the transgressive Kaula tradition clashed. By the tenth century, two profoundly opposed schools—the dualistic Śaiva Siddhanta and the nondualistic Trika and Krama”—dominated the Śaiva landscape.

The nondualists, who believed that the world and people are only the play of a universal consciousness-self, operated from within transgressive cults “tainted” by the cremation grounds’ Kāpālika culture and the Kaulas’ erotic-mystical soteriology.

The Kashmir Aivism Nondual School combined transgressive non-dualistic traditions with traditional dualistic Śaiva Siddhanta. The non-dualistic system assimilated transgression components, making them less offensive to the orthodox.

Abhinavagupta was a famous Kashmiri Śaiva theologian (c. 975–1025 CE). He wrote many Trika and Krama commentaries and philosophical and aesthetic works.

later the hardcore techniques with softcore meditation exercises. This may explain the tantric distinction between “left-handed” or unorthodox practice (vāmācāra) and “right-handed” or orthodox practice (dakiācāra). Tantric practice’s more provocative aspects were also neutralized by Buddhist traditions, which transformed it from external rites to inward imaginations.

The Nth, or “Split-Ear” Kānphaya tantric tradition, was the last to develop. The Pupatas and Kplikas were heterodox Śaiva renunciant orders that influenced medieval tradition. Some Nāths were Vaiāava, Buddhist, Sikhism, and Islam-oriented, but most were Śaiva. It became popular in the 12th or 13th centuries, “to the extent that by the nineteenth century, India’s British conquerors occasionally mistook the term “yogi” to refer to a member of one of the Nth Yog orders.”

The great adept Goraka or Gorakhnth is said to have given this cult the Haha yoga tantric scriptures. The 14th- and 15th-century Gorakasahitā, Khercarīvidyā, and Hahayogapradīpikā were tantric scriptures they wrote. Though late, they have shaped modern yoga. Their tantric yoga involves breath control (prāyāma) and complicated yogic exercises to retain and transmute sexual fluids.

Conclusion

During a pleasurable experience, tantra or tantric sex aims to develop spiritual or energy connections. This technique is slow, and achieving orgasm is not usually the goal. Instead, it is about having a strong and enlightened connection with your partner or with yourself. It consists of breathing, sounds, and motions to stimulate sexual energy.

Tantra isn’t merely a sexual practice. Several spiritual notions are contained within this Eastern philosophy. Breathing, yoga, and meditation are tantric activities that can improve sexual vitality. A prevalent misperception regarding tantric sex is that it entails untamed, unrestrained sexual encounters. Tantric practices might open you up to new sensations, but they are also mental and spiritual practices.

Another myth about tantra is that a partner is always required. Although many couples engage in tantric sex together, it can also be practiced alone. A tantric experience does not necessitate genital touch or intercourse. In tantra, Sexual activity can increase your experience, but you can also practice tantra to feel more connected to your own mind and body and to provide yourself with pleasure.

Excerpts and notes are taken from Dr. Uday’s “Mandala of Sex” and David’s Tantric Traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism.

Disclaimer: This information is for Knowledge and educational purposes only.

The author’s views are his or her own. The facts and opinions in the article have been taken from various articles and commentaries available in the online media and Eastside Writers does not take any responsibility or obligation for them.

Note: Contact our Writers at www.eastsidewriters.com for writing Blogs/Articles on any niche. We have experts in various domains from Technology to Finance and from Spirituality to Lifestyle and Entertainment.

Originally posted 2022-12-13 13:05:17.

Pingback: Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder - Its Cause and Remedy

Pingback: Astounding Benefits Of Wearing Black Thread On Feet - Eastside Writers

Pingback: Exploring the Complex Realities of Frotteuristic disorder: The Shadows of Non-Consensual Burning Desires - Eastside Writers

Pingback: Mysteries of Epididymal Hypertension: Knowing the Secrets of the 'Blue Balls' Phenomenon - Eastside Writers